What's wrong with development economics

Reflections on a recent panel

What is wrong with development economics

Here is a fact: Resource poor countries are research poor and representationally poor. But why?

The other day I participated in a panel on what’s wrong with development economics, with Markus Goldstein at CGD, Leonard Wantchekon (Princeton) and Orianna Bandiera (UCL). Markus and Juan Menendez have written a blog on the panel, which highlights problems with the 3Rs: Rates (too little work on development), Relevance (very little concordance between what policymakers say they need and what is actually done) and Representation (most of the work is done by people in institutions outside the country).

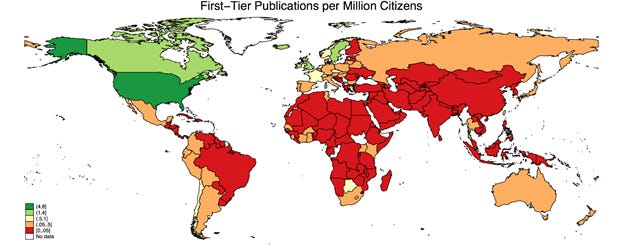

I want to bolster the rates and representation arguments with a couple of pictures and tables.

Resource Poor is Research Poor

Figure 1 is based on data from Das and others (2013). It shows just how few papers are published outside the U.S. (and some parts of Europe) in the top economics journals. For example, over the 20-year period from 1985 to 2005, there were 34 papers on any Sub-Saharan African countries. Numerous authors have extended our work, but the results do not change. Markus pointed out that if you squint in just the right way, you can see some improvement (38 papers over the last 10 years from SSA in the top journals), but in the journal with the greatest representation—the American Economic Review—papers from Sub-Saharan Africa still account for just 1% of all papers. Resource poor places continue to be research poor—and not much has changed since I last worked on this.

Figure 1: Resource Poor is Research Poor

Poor resources = poor representation

Figure 2: Editors of major journals who have a substantial connection to a low-income country

American Economic Review: NONE

American Economic Journal: Applied Economics: NONE

Journal of Development Economics: THREE

I did not make a figure because there is no complex information to convey, but you get the idea. I had expected very little representation in the AER and AEJ, which are both journals of the American Economic Association, still very much a U.S. focused institution. And that is indeed the case, without a single editor with a substantial connection to a low-income country.

But it is very troubling that the premier journal in development, JDE, has three editors with a substantial connection to a low-income country, not a single one from Africa or the Middle-East and not a single one based in India or China? (People may/will disagree about how I classify `substantial connection’ so I invite them to look at the full list of editors on the journal website and DM me if I got it wrong; I defined substantial connection as someone who is either located in or studied in an institution outside U.S./Europe.

An answer then to the question of what’s wrong with development economics is that the field has not managed to increase representation from the very countries where the work is done.

Why?

One possibility is that this reflects bias and discrimination. Indeed, Leonard Wantchekon provides a compelling example in the panel of his attempts to increase African representation in the Econometric Society, which is very low despite the fact that there are candidates with better records than those who are already members. I do not disagree that bias and discrimination are part of the problem, and indeed there are multiple papers that demonstrate racial bias in academia.

But what does not sit right with me is that the editors I know are all just as worried about the lack of representation as the panel. These are editors who have spent months/years in low-income countries with strong connections to academicians in the countries they work in, and they have been forced to conclude that the pipeline is just not strong enough to guarantee a steady stream of editors from low-income countries. Too see what I mean, if you look at articles published in the JDE, a point that Markus makes in his blog, very few are written by people with substantial connections to the country they are writing on. The fact is that, even as development economics has been singularly successful at solving one of the hardest problems in economics—increasing representation among women--it has failed at increasing representation from low-income countries.

Rather than a story of bias or discrimination (which conditions on the academic standing of the researcher), my worry is that the more pernicious problem is a bias in epistemic authority. By which I mean that we are OK with wider representation only as long as the research methods agree with our own epistemological approach.

1. The bias in epistemic authority undercuts the whole point of wider representation, which is to bring on board people who approach problems in an entirely different way.

2. The bias in epistemic authority is not `OK because our approach is better.’ There is no questioning that the epistemic approaches favored over the last 20 years have yielded substantial gains in our understanding of low-income countries across a host of topics. But for many problems the research has become increasingly technically sophisticated and increasingly less contextually aware. Fundamental mistakes are being made because researchers do not know enough about the context they are working in. Worse, there is often no knowledge-based reason for why our approach is preferable: Much of our epistemic authority has necessarily flimsy foundations.

3. The bias in epistemic authority seems to come from a place of some arrogance and some forgetting. We believe our approach is superior. We forget that whatever approach we take is cobbled together from a set of tacit agreements arrived at over years of research. Agreements that allowed us to make progress by walling off a set of problems `to deal with later.’ But by now, many of those tacit agreements have been forgotten and the conversations that wider representation surface often reflects the fragility of those agreements. We would be fools if we did not foster those conversations and if we did not listen carefully.

Look, I am not claiming that the regulatory and epistemic authority that is implicitly played out in the journals has not brought us substantial gains in knowledge over the last two decades. It has, and I am not arguing that we should go back to the way development economics was practiced, say, in the 1980s.

What I am saying is that even though the very best in the field always combine a deep contextual understanding with technical mastery, we are moving/have moved to a situation where deep contextual understanding can be sacrificed on the altar of technical mastery, but not the other way around. I feel that is a huge mistake that we are making.

The bias in epistemic authority implies that editors who are `different’ and who approach questions in a fundamentally different way will not pass muster with our peers. We, and our editors, are then stuck with the problem of adjudicating epistemic authority in a manner that must be acceptable to the majority of the discipline, in a situation where the peer composition has clearly shifted towards very little representation among those from low-income countries.

That, I fear, is a structure that can lead us into indefinitely long periods of increasing irrelevance.

I really like the framing of the problem as one of epistemic authority allocation. Your point about editorial boards aligns with what we see in authorship data as well. Of 175 authors publishing on Sub-Saharan Africa in the top five journals (2015–2025), only 19 (10.8%) had a substantial connection with Africa (as you define it), and just 9 (0.5%) were affiliated with an African institution. These figures suggest that increasing the number of African scholars working on Africa will not by itself erase the epistemic bias. Much of the “pipeline” tends to reproduce the same structures of authority. In that sense, representation without agenda-setting power or a progressive paradigm shift risks further disconnecting knowledge production from on-the-ground priorities, which can ultimately undermine academia's credibility.

The diagnosis that contextual understanding can be sacrificed to technical mastery is quite remarkable - my question is why not encourage more regional journals and prescribe articles published in those journals to students and bring them into discussion in panels, in the class room , and in conversations ?