The problem with the privatization debate in education

(#2 in “Conversations with The Public Pessimist")

The Public Pessimist: A person who believes that the public sector sucks all our money into a black hole of corruption and inefficiency and is incapable of delivering even the most rudimentary of services.

The rationale for using public funds to support private schooling is customarily based, at least in low- and middle-income countries, on the following three-step argument.

Step 1: The quality of education is better in private schools.

Step 2: The cost of providing education is lower in private schools.

Step 3: Therefore, funding private schools will buy us higher quality at a lower price.

That 3-step argument initiates my conversation with The Public Pessimist, my unusually well-read fictional counterpart. This 2nd post in the series assesses what we truly know about quality and costs in private and public schools, which correspond to Step 1 and 2 in the 3-step argument.

I. The Problem with Quality Comparisons: The Mean does not Mean Much

The Public Pessimist: Help me here. Children in private schools consistently report higher test scores than in public schools. The cost of schooling in the private sector is substantially lower than in the public sector. So, what is the problem? Why not just fund private schools with the public purse and leave it at that? Or are you going to argue that these effects are not “causal” because they do not account for the fact that children attending private schools are `different’ from those attending public schools?

Me: What a great place to start. The usual problem with straightforward comparisons of performance among children in the public and private schools is indeed “The Selection Effect” or the fact that children are not randomly assigned into public and private schools. If children attending private schools come from better resourced families or are faster learners, to the extent that these differences are unobserved and therefore cannot be `controlled’ for, they will indeed confound the mean differences. This problem is considered to be so pervasive that much of the research on private schooling is singularly focused on addressing such selection effects. However, a fair summary of the literature is that doing so does not overturn a private school advantage; it does appear that children in private schools either report higher or very similar test scores to those in public schools. So, for the rest of this post, I will assume that the selection problem has been solved and we can therefore treat our estimates “as if” children were randomly allocated to public and private schools. From that starting point, I want to surface a more fundamental problem.

The Public Pessimist: So, just to make sure that we are clear. The issues we will discuss assume that selection effects have been satisfactorily dealt with—and you will argue that there are still fundamental problems that remain. I am intrigued.

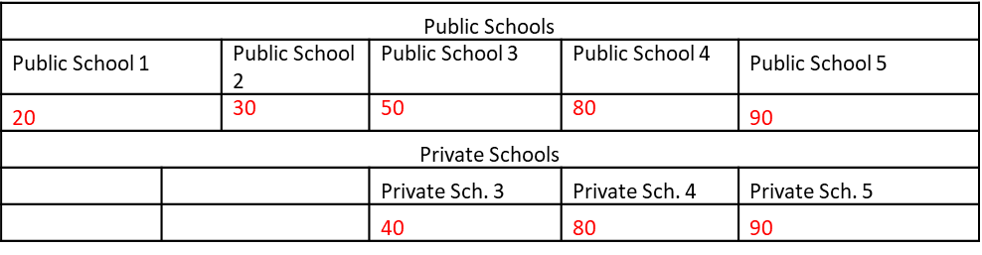

Me: I want to take you to a village in Punjab, Pakistan, the world’s 12th largest schooling system, that is not “special” in any way, but is actually quite typical of many villages in South Asia and most urban and peri-urban areas in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Indeed 70% of the population in Punjab lives in villages like the one shown in our stylized example in Table 1. The village has 8 schools, 5 of which are public and 3 are private schools. Our measure of school quality, test scores are shown on a 0 to 100 scale as numbers in the cells for each school. And just to show clearly where each school is on the quality ladder, I have called them Public School 1 to Public School 5 and Private School 3 to Private School 5.

Given these data, would you claim that the private schools are “better”?

Table 1: Stylized Example of School Quality in one Village

The Public Pessimist: Well, of course. Taking you at your word that the selection problems have been fully addressed, the average (mean) test scores in the private schools is 70 and in the public schools it is only 54.

Me: And that difference in means is precisely what you would find if you tested a random sample of children and were fully able to purge the selection effect from the mean differences. We thus confirm that in our stylized village, Step 1 of the argument holds: Test scores, purged of selection effects, is higher for children enrolled in private compared to public schools.

But here is the problem: This mean difference is of limited interest because it corresponds only to the policy of placing children randomly in a public or private school. Even if that were remotely feasible, it is completely unclear why that would be desirable. Worse, if the government were to use mean differences to guide policy it could just shut down schools 1, 2 and 3 in the public sector, thereby raising the public schools’ average score to 85 and beating the private sector.

The Public Pessimist: But that makes no sense. What if Schools 1 and 2 are in the poor parts of the village and those kids would have nowhere to go if you shut those schools down?

Me: Exactly! Suppose that parents care both about test scores and the distance to school and we are trying to understand what would happen if the government shut down Public School 1. What we really want to know are the specific schools those children will now attend and whether there are some who would dropout—and that depends on how parents choose among schools. Or, consider a policy that funds children in public schools to now attend private schools for free as does India’s Right to Education Act. If as a result of this policy, children leave Public School 5 and go to Private School 3, it would lead to lower test scores. We do not know whether this is likely, but you see the point: The estimate we are interested in always has to consider the specific public school that children will leave and the specific private school they will attend.

The Public Pessimist: Let me get this clear. We assume that parents care both about test scores and distance to school. I get that. Is the point then that the government should then also care about test scores and distance in deciding whether a school is good?

Me: Ah. That is a very deep question. Absolutely, the government could privilege what parents care about and, in this example, that would include both test scores and distance. But the point I want to make is that even if the government only cares about a single outcome such as test scores, as long as there is variation in what test scores schools produce within the public and within the private sector, the impact of any policy that induces children to switch schools will depend on the exact schools they leave and the exact schools they go to. And that, in turn, depends on what parents care about when they choose schools.

The Public Pessimist: I guess I kind of see the problem but not really. You are saying that the mean is meaningless, but it seems to me that you buried a lot under the rug. For instance, if test scores were like in my alternate Table 2 below, such that there is no variation in test scores within sectors, you could shut down any public school and still have the private sector doing better. Similarly, vouchers that allow children to leave the public sector will always increase test scores. In fact, I think that if children are randomized into schools, these scores would look more like my table rather than yours. And aren’t you forgetting about enrollment? If School 5 in the public sector in your example had only 5% of public enrollment and School 1 had 80%, wouldn’t you want a weighted average, weighted by enrollment?

Table 2: The Public Pessimist’s alternate stylized description

Me: Table 2 is a great counter-example and although it will not solve all the problems (for instance, we still do not know what the private schools would look like if they were in exactly the same location) it puts us on much firmer ground. In Table 2, any switches between public and private schools increases test scores. But it is not clear that why the data on the ground should look like your Table 2, rather than my Table 1: Even when children are randomized into schools, schools have different cultures, different teachers, different head teachers etc. etc. Whether the situation looks more like Table 1 or Table 2 is ultimately something that we will have to learn from the data.

Turning to your second point—absolutely, you could compute the enrollment-weighted test scores. But if the scores look like my Table 1, changing the enrollment shares can take us all the way from a weighted mean difference of +70 in favor of the private sector to +50 in favor of the public sector. So, much will depend on how we interpret the enrollment shares. We will return to this in the 3rd post in the series and show that yours is indeed a sound proposal because (with one tweak), we can provide a micro-foundation based on utility maximization that justifies the use of something like weighted market shares. But let us hold on to that for the moment.

The Public Pessimist: Oh, I see what you did. For the +70 in favor of the private sector you assumed that all the kids in the public sector went to School 1 and in the private sector to School 5 and then for the +50 in favor of the public sector you made all the kids go to School 5 in the public sector and School 3 in the private sector. Clever. I guess I see the problem. If school quality is different within sectors, then it is going to be quite hard to even describe what the public-private difference looks like. Some schools are better in the private sector, some may be really bad in the public sector but the private sector advantage depends on what comparison we want to make. If I were to think about it in the language of causal impact, you are saying that instead of a single treatment, there are many treatments depending precisely on what specific school in the public sector is being compared to what specific school in the private sector. And that is not the same as heterogeneity of the treatment effect, which arises because different children may experience different gains. Right?

Me: Yup.

The Public Pessimist: I see. But then the empirical observations become really important: Does the data look like Table 1 or Table 2—are there really big differences in school quality within the same village and within the same sector?

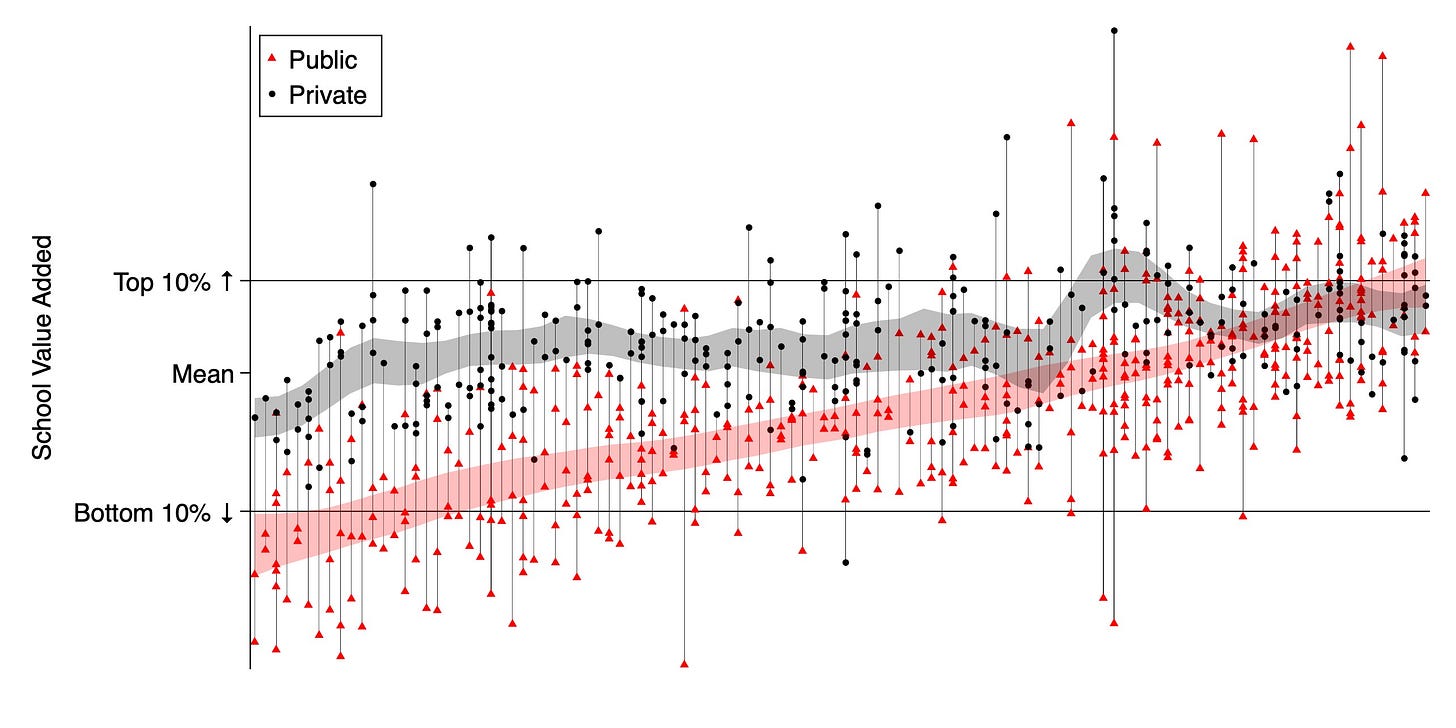

Me: I just finished a paper with Tahir Andrabi, Natalie Bau and Asim Khwaja that tries to get at this question using the LEAPS data from Pakistan and the short answer is that we are very much in Table 1 world, not in Table 2 world. Here are some key findings and one of the key figures in the paper, showing the quality of every school in each village in the LEAPS village. Both in the description below and in the figure, our measure of school quality is School Value Added or SVA, which is defined as the gain in test scores that a randomly selected child would experience in a given school over a year:

There is “substantial variation in school quality, much of which is within villages.” The most striking example of this is that, accumulated over 5 years, the difference in test scores between children in their current school and the best school in the village is the same as the test-score gap between high and low-income countries!

There is also “considerable variation within both the public and private sectors.” We show that (a) school quality is more varied in the public compared to the private sector and (b) that excess variation arises because there are some very low-quality schools in the public sector—at the top end, public and private schools are very similar.

Given this massive variation, the “private school premium” completely depends on the precise comparison that is made. For instance, you could say that “On average, attending a private school increase mean yearly test score gains by 0.15 sd relative to a public school.” But you could also say that “moving all public-school children to the best private school increases test scores by more than 0.25 sd.” And you could also say that “moving children from the best public school to the worst performing private school in their village would decrease test scores by 0.07sd. As we write: “This range of effects clarifies that the approach thus far in the literature from low-income countries of estimating a single private premium can be misleading and will necessarily only be valid for a specific reallocation of children.”

Figure 1: Variation in School Value-Added within the 112 LEAPS villages

Description of the figure from an article I wrote for Education Next: “Each vertical line in the figure represents one of the 112 LEAPS villages. Schools in each village are arranged on the line according to their school value-added, with public schools indicated by red triangles and private schools by black dots. The red band tracks the average quality of public schools in the villages, from weakest to strongest, and the gray band shows the average quality of private schools in the villages. The private schools are, on average, more successful in raising test scores than their public-sector counterparts. As is clear, however, every village has private and public schools of varying quality, and the measure of any “private-school premium” depends entirely on which specific schools are being compared. In fact, the study shows that the causal impact of private schooling on annual test scores can range from –0.08 to +0.39 standard deviations. The low end of this range represents the average loss across all villages when children move from the best performing public school to the worst-performing private school in the same village. The upper end represents the average gain across all villages when children move from the worst-performing public school to the best-performing private school, again within the same village”

The Public Pessimist: I must admit that looks a lot like Table 1. But that is just one study. What about other countries?

Me: The methods that we use were first developed by Josh Angrist, Parag Pathak, and Chris Walters in their pioneering work on school quality in the U.S., where they find similarly large variation within metropolitan areas. You would imagine that by now we would have similar data for many low- and middle-income countries with tons of studies that tell us whether we are in Table 1 or Table 2. But, actually, ours are the first such estimates. Part of the reason for this was that people were very focused on solving the selection problem and did not worry about this kind of heterogeneity, but part of it was also because we just did not have the data that we needed to estimate school value added purged of the selection effects. The LEAPS data that we collected and use for this paper are quite unique in testing the same children multiple times over their schooling years in a comparable manner. If data like this are collected in more countries in the coming years, we can start to understand whether schooling markets look like Table 1 or Table 2.

The Public Pessimist: I see the point you are making. You are saying that even if Step 1 in our three-part argument is correct when you compare the means of test scores across children, that comparison itself is flawed because of the variation in quality within the public and private sectors. Given this variation, the right estimate has to be linked to the policy under consideration and different policies will lead to different estimates of the public-private difference depending on how children switched schools. But then, to understand the impact of widely advocated policies, we need some prediction of precisely how children will switch schools under the policy.

Me: That is exactly right. For instance, another way to think of the quality of a school is the difference in test scores in the village with and without that school, which will then depend on what other school(s) children will attend once a school shuts down.

The Public Pessimist: And is there a way to get at that without actually shutting down the school?

Me: Yes—or at least, we can try. That is the next post in the series!

II. The problem with Costs

The Public Pessimist: OK. I will give you that quality comparisons are complicated. But that still leaves the cost question unanswered. You and others have shown that the costs of educating children are much lower in the private sector. So perhaps we just turn all those 5 schools in the public sector over to the private sector; Even if quality does not improve, costs will plummet and we can use that public money elsewhere or even invest it back in the schools.

Me: Ehh…kind of. The simple kinds of calculations we and others have done for South Asia is to total the costs for children in private schools and in public schools and compute the per-child costs. And it is completely true that, computed in this way, the per-child cost is much lower for children in private compared to public schools. But while that simple comparison is correct, we would be wrong to think that the costs differences reflect differences in technical efficiency or the idea that costs are lower in the private sector because they are producing the same (or better outputs) using fewer inputs.

The Public Pessimist: Huh? Sorry, this one sounds like a completely whacky argument.

Me: Not at all. The first problem is the older one we just talked about—public and private schools are not in the same location. So, if the public sector is setting up schools in remote villages where operational costs are higher and enrollment is lower, per-capita costs will also be higher. Empirically, in South Asia it turns out that this problem may not be that important and it is a second, subtle issue that is really driving the bulk of the cost differences.

That second problem is as follows. Usually, when we say one firm is more productive than another, it is a statement of the ability of the two firms to convert inputs to outputs and not a statement of the factor prices—say, the wage rate or the cost of capital—that the two firms face. This makes sense because the theoretical foundation of these comparisons is a competitive market where both firms face the same factor prices.

But in the case of the public sector—and this is particularly true for India and Pakistan—the factor prices are completely different because teachers in the public sector are paid 4-5 times as much as teachers in the private sector. Now, when making cost comparisons you also have to account for differences in the factor prices and it turns out that the entire reason why education is more expensive in the public sector is because of differences in the factor prices. In fact, if you simulate what happens when you use private sector wages (appropriately adjusted for differences in teacher characteristics) in the public sector, the cost of education would be lower in public than private schools. Bizarrely, the cost of educating a child in the public sector is much higher—but the public sector may actually be more productive!

If this is all super confusing here is an example that helped me work through it. Think of 2 firms making shoes. They both hire one worker and pay their single worker $10 per hour. Firm 1 makes 100 shoes using 10 hours of labor, so the cost is $1 per shoe. Firm 2 makes 50 shoes using 10 hours of labor, so the cost is $2 per shoe. Clearly, Firm 1 is more productive. But what happens now if Firm 1 is owned by the Das Kapital Ventures who really care about the workers and, give them a $500 bonus every day so that they have a better life. From one perspective, the “cost” per shoe in Firm 1 is now huge--$6 per shoe—and clearly Firm 1 is no longer “competitive” in the sense that no profit maximizing entrepreneur is going to be willing buy Firm 1 with the stipulation that they must pay their worker the same bonus every day. But Firm 1 is still more technically efficient because it still produces more output with the same input. The fact that Das Kapital Ventures chooses to pay their workers a bonus is irrelevant for this argument.

Of course it is even more complicated. If we really want to make the statement that public (or private) schools are more productive, we would have to realize that if factor prices were actually the same, inputs would also change. This is the question of economic rather than technical efficiency. Theoretically, we could try and estimate what the private sector would do if it had to pay its teachers 5 times as much and see if they could produce better test scores at lower costs. But that counterfactual is so far removed from the reality that it is impossible to know what would happen—we never observe overlaps in public and private sector wages, so even trying to answer the question of how a private school would behave under public sector wages or vice-versa requires totally wild extrapolation. It is, essentially, an unanswerable question in the South Asian context.

The Public Pessimist: These arguments are driving me crazy. Isn’t it still the case that if I take a public school and give it to a private operator, the private operator can run it at a lower cost?

Me: If they fire all the teachers and bring their own at lower wages, sure. But now we are firmly out of economics and into politics. In the sense that if teachers’ wages are determined as part of a political process within a democratic framework, it is akin to saying that we are all willing to pay higher taxes to give teachers a bonus every day. And it is not just teachers—in countries like India and Pakistan, most public sector employees are paid far more than they would be in the equivalent private sector job. This is why we have hundreds of thousands of applicants for every public sector job.

Is that the right way to do things? Should we have lower wages for government jobs and perhaps a much larger public sector? These are all great questions but outside the purview of our discussion and part of a much larger democratic conversation around the size of the government and the compensation structure. For us, the key observations are (a) that these wages are indeed determined through a democratic process with an institutional structure (in India, the finance commissions) and (b) therefore, it is quite likely that attempts to decrease teachers’ wages by stealth, which is what this kind of privatization really tries to do will eventually run into the same democratic trade-offs that determined the size and wages of the public sector to begin with. And indeed, we see that successive attempts to do a run-around the structure of wages eventually run aground as teachers go on strike and governments start putting in laws that say that institutions receiving public subsidies are subject to the same wage requirements as those in the public sector.

The Public Pessimist: So then, the point in yours and others work of showing that these high teacher wages do not result in greater learning was….?

Me: …Primarily to demonstrate exactly that. At the time we were writing that paper (Natalie Bau and me), there was an argument that higher teacher wages were necessary to both bring in better teachers and help them teach better. We showed that this argument was incorrect—teachers hired on temporary contracts at 30% lower wages had learning outcomes that were just as good, if not better, with no negative impact on the quality of new hires. At the same time, Joppe de Ree, Karthik Muralidharan, Menno Pradhan and Halsey Rogers showed that in Indonesia, where (unlike in Pakistan) the wages were really low to begin with, doubling the wage again had no impact on test scores. Between the two papers, the question goes right back to the political process, where it belongs, rather than incorrect arguments around technical or economic efficiency. It is for researchers to clarify the arguments and impacts of policies, but it is for politicians to examine the broader repercussions of policies that adjudicate among different interest groups.

The Public Pessimist: And that seems like a great place to stop. To summarize because this is a lot to take in. First, there is no simple quality comparison that we can make between the public and private sector—instead, there is substantial quality variation within each sector. Second, even the cost arguments are less clear than what they appear to be at first—things like contracting-out to the private sector are going to be short-term fixes but not a long-run solution because the imperatives that lead to high teachers wages in the first place will eventually return. Hope I got that right—no wonder they call economics the dismal science.

But where does that leave us? Can we actually make comparisons between public and private schools? And what policies should we be thinking of in this domain? We will take that up in subsequent posts.

References

The key idea that school quality varies tremendously within the public and private sector is shown in our new paper Andrabi, Tahir, Natalie Bau, Jishnu Das, and Asim Ijaz Khwaja. Heterogeneity in school value-added and the private premium. Forthcoming in the American Economic Review. You can read a brief on it, written for the Cato Institute at https://www.cato.org/research-briefs-economic-policy/how-much-does-school-quality-vary and you can listen to a podcast that I did on this work with Jason Silberstein at RISE at https://riseprogramme.org/podcast/jishnu-das.html. You can also read a broader piece that I wrote, Das, Jishnu. "No School Stands Alone." Education Next 23, no. 3 (2023).

Our work borrows from, and extends, the work on school value added started by Josh Angrist, Parag Pathak and Chris Walters and we learnt a lot from reading Angrist, Joshua D., Peter D. Hull, Parag A. Pathak, and Christopher R. Walters. "Leveraging lotteries for school value-added: Testing and estimation." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132, no. 2 (2017): 871-919.

The post also references a paper I wrote with Natalie on teacher value-added, Bau, Natalie, and Jishnu Das. "Teacher value added in a low-income country." American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12, no. 1 (2020): 62-96, and the work be de Ree and others on the impacts of raising teachers’ wages in Indonesia, De Ree, Joppe, Karthik Muralidharan, Menno Pradhan, and Halsey Rogers. "Double for nothing? Experimental evidence on an unconditional teacher salary increase in Indonesia." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133, no. 2 (2018): 993-1039.